When officials in Montgomery county, just outside Washington DC, decided to electrify the local bus fleet, they turned to a local utility. The amount of power required to convert its Brookville bus depot into a charging hub, the utility said, would require not only a new electricity substation, but significant time and money.

Instead, Montgomery opted for a different solution. It entered into an agreement with AlphaStruxure — a joint venture between France-headquartered Schneider Electric and US private equity firm Carlyle — to build and operate a microgrid to power its 70-strong bus fleet. The 6.5 megawatt (MW) onsite electricity network started operations last October. It consists of solar photovoltaic canopies, battery energy storage, charging stations and software that allows AlphaStruxure to remotely coordinate the system for optimal performance.

Advertisement

The Brookville Smart Energy Bus Depot is an example of how “microgrids can bring power to places where the grid can’t do so readily or quickly,” says Jana Gerber, Schneider Electric’s president of microgrids, North America. It is also a cheaper solution: with Carlyle providing the financing, there was zero upfront capital commitment required by the county, and no need for expensive grid upgrades.

Longer, stronger, smarter

By providing onsite power, the Brookville microgrid reduces pressure on the US electric grid which, like others around the world, is not yet fully fit for the green economy of the future. As more countries commit to net-zero emissions by 2050, electricity networks require a massive upgrade to make them longer, stronger and smarter. This encompasses both transmission lines — the energy highways which transfer power over long distances — and distribution networks which handle last-mile delivery.

The reasons are manifold. As intermittent renewables account for a greater share of the generation mix, and polluting but reliable baseload power is phased out, grids must become more flexible to keep demand and supply in constant balance. The proliferation of ‘prosumers’, or customers who produce their own solar power and sell the surplus into the grid, means cables must facilitate bidirectional flow. Meanwhile the electrification of mobility and heating means electricity demand in the EU will double by 2050, and will soar by 66% in North America, compared to 2022 levels, according to consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

And it is not just the increased load that requires grid modernisation. “The dynamic of the load is changing. Electric vehicle (EV) charging is different to turning on your stove,” says Fahimeh Kazempour, head of grid modernisation at Wood Mackenzie.

These capabilities are beyond what the antiquated cables running across much of the Western world can provide — including in the US, where 70% of transmission lines are more than 30 years old. One solution is to transform conventional power lines into so-called ‘smart grids’ via an array of digital solutions spanning from sensors to control algorithms that optimise the potential of existing lines.

Advertisement

However, grids also need to be extended. Networks have been designed around traditional power plants being located close to cities and other demand centres, while renewable generation occurs where the resource is available or the land is cheaper. That entails longer, higher voltage lines to transfer electricity where it needs to go.

Big investment

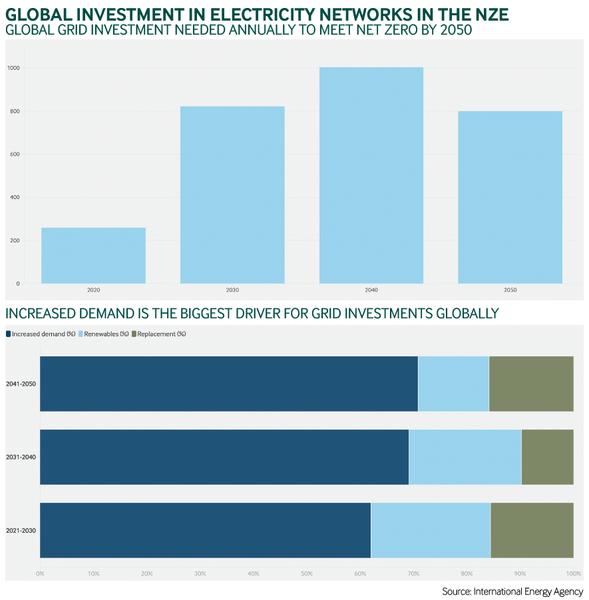

Meeting net-zero targets by 2050 requires $21.4tn worth of investments in grids globally, and more than doubling their collective length, according to BloombergNEF. Grid operators in developed markets are upping their capital pledges. Wood Mackenzie research shows 25 major US utilities have proposed $36.4bn investment in grid modernisation since 2018. Italy’s Enel has earmarked €15bn for its networks globally over the next three years, while in March German 50Hertz committed to spend €8.7bn on its German grid until 2028. But collectively, the sector is woefully behind schedule. The International Energy Agency (IEA) says annual grid investments must more than triple from current levels to hit $820bn by 2030 and $1tn by 2040.

For all the focus on EVs and renewables generation, the infrastructure connecting those two worlds has fallen by the wayside, and is creating a bottleneck in the green transition. A Princeton University study published last year found that 80% of the potential emission reductions set to be delivered by the US Inflation Reduction Act in 2030 will be lost if transmission expansion continues at the current pace. Australia’s transmission roadmap requires much of its infrastructure to be built in the next decade.

However, Marija Petkovic, managing director of advisory firm Energy Synapse, says there is a “significant risk that the required investment … will not be delivered on time, which puts the clean energy transition at risk.” Meanwhile in South Africa, renewable energy auctions last December saw the government award only 20% of the capacity it had originally intended due to insufficient grid capacity.

Monopolising modernisation

These situations lay bare the fact that traditional approaches to grid investments are not unleashing changes at the necessary pace. While no two electricity networks are the same and each has a different regulatory set-up, “the model pretty much worldwide is the same” when it comes to grid investments, says Simon Hodson, CEO of Gridworks — an Africa-focused investment platform owned by British International Investment, the development finance institution of the UK.

State-owned or privatised grid operators have a monopoly over their network. Their investment plans are approved by the electricity market regulator, and they generate a return on that investment by a higher government-approved tariff passed on to customers.

There is a bit of a tussle between what’s in the best interest of the business, and what’s in the best interest of the industry

But utilities’ monopoly rights, combined with hesitancy to increase customers’ bills, have created some inertia when it comes to transmission upgrades. “They are inherently risky and capital intensive — neither of which are very attractive to utilities that are trying to produce a profit, deliver a dividend and run an efficient business,” says Lisa Lambert, president of National Grid Partners, the British utility’s venture capital arm. “So, there is a bit of a tussle between what’s in the best interest of the business, and what’s in the best interest of the industry and ultimately the consumer.”

Luciano Martini, chair of the IEA’s International Smart Grid Action Network, notes that “to a large extent, innovation lies on the shoulders of the transmission and distribution system operators … [but] given the magnitude of the investment needed, and the rapid pace of change required, many business models in the energy sector may not be up to the challenge.”

Tinkering around the edges

A new breed of private players is now trying to plug the hole and shake up traditional approaches to grid investment. AlphaStruxure, the joint venture behind the Brookville bus terminal, is an example of one of them. These partnerships between financial investors, which front the capital, and tech firms, which engineer the power system, provide microgrids as a holistic solution to industrial customers that use large amounts of electricity. This model involves the design, build, ownership, operation and maintenance of the microgrid in exchange for the customer’s payment per kilowatt hour — not dissimilar to a regulated utility. However, the joint venture also manages and advises on the interaction between the customer’s various energy assets to minimise costs and carbon output. Thus, it is called ‘energy-as-a-service’ (EaaS).

In the US, Schneider Electric has a similar joint venture with Huck Capital called GreenStruxure, while in India it provides EaaS in partnership with Singaporean investment company Temasek. Also in the US, financial investors Ares and Macquarie have similar arrangements with Renew Energy Partners and Siemens, respectively. According to Wood Mackenzie, EaaS structures accounted for 44% of US microgrid investments last year, up from 18% in 2019.

“[This is] a key way that private money is going into funding grid infrastructure,” says Ben Hertz-Shargel, the consultancy’s global head of grid edge, which is energy parlance for grid innovations that exist in proximity to the consumer. The trend is being spurred in part by the rollout of charging infrastructure for power-hungry EVs. “The electrification of mobility is driving a lot of opportunity and need [for microgrids],” adds Ms Gerber.

Venture capital is also backing start-ups that help improve the performance of existing transmission infrastructure. National Grid Partners, which has been operating since 2018, invests in early stage ventures that are “thinking outside the box” to give utilities a cheaper and quicker alternative to replacing their grids, says Ms Lambert. “Start-ups are innovating as they understand the quandary that utilities, regulators and governments are in. These are massive investments, so you don’t enter into them lightly,” she says. Of the 40 companies in its portfolio, 80% are in proof of concept, pilot or deployment at National Grid’s transmission networks across the UK and US.

One of them is LineVision, a US-headquartered firm that provides dynamic line rating (DLR) technology to grid operators across North America, Europe and Asia Pacific. An example of smart grid technology, DLR uses sensors to assess the real-time capacity of transmission lines, which increases during cooler weather and reduces when it is hot. Utilities usually make “worst-case assumptions” to ensure they do not overheat, says LineVision CEO Hudson Gilmer. DLR allows them to monitor and put more power through transmission lines when weather conditions permit, allowing them to operate closer to their physical capacity.

Research by the International Renewable Energy Agency has found that DLR allows for increased integration of variable renewable energy by reducing congestion. Applying LineVision’s technology to one UK transmission line carrying significant offshore wind power increased its capacity by more than 50% and eliminated virtually all curtailment, says Mr Gilmer.

An innovation spearheaded further upstream which helps grids absorb more renewables is battery energy storage systems (Bess). These connect to national grids and help smooth intermittent renewables’ impact on the network’s frequency by drawing power when supply is strong and releasing it onto the grid when demand peaks. Bess infrastructure also provides a source of standby power to ensure it keeps flowing when there would otherwise be a system outage. Like DLR, this gives grid operators the confidence to operate networks closer to their full capacity.

One of the pioneers of this technology is French group Neoen, which started storage activity in 2015 and is now operating or constructing Bess solutions in France, Finland, Sweden, El Salvador and Australia. “Initially, getting grid operators to trust a private counterparty to build something new, connect to the grid and say ‘don’t worry, when there is an accident I’ll make the grid work’, was a real challenge,” explains Romain Desrousseaux, Neoen’s deputy CEO. “But we succeeded … notably in Australia.” Indeed, the country is Neoen’s biggest market, with eight projects including the 300MW Victorian Big Battery, which it claims is among the biggest in the world.

The large percentage of renewables in Australia’s electricity mix — notably in the state of South Australia where it hovers around 70% — has forced its grid operators to adapt quicker than elsewhere. In Europe, for instance, where that figure is closer to 20%, Mr Desrousseaux says “proving to the grids that these batteries are a good solution … is still not an easy exercise.” However, he says things are evolving and is confident Neoen can convince more network operators of the technology’s effectiveness.

Poles and wires

These nimble solutions are a valuable step towards greening electricity grids, but they are not sufficient to meet net-zero targets. Rather, they buy more time to construct longer and stronger cables. A case in point is Idaho Power, which wants to eliminate fossil fuels from its electricity network in the US’s northwest by 2045. “Of course, you can use technologies to take better advantage of existing infrastructure,” says its chief operating officer, Adam Richins. “But we won’t meet [our] goal unless we build a variety of different transmission lines … to get clean energy where we need it to go.”

The US grid is managed by a patchwork of utilities that historically had right-of-first-refusal for grid extensions within their area. Some US states scrapped this from 2011, which has paved the way for cheaper and quicker transmission projects. “When there is competitive bidding, developers can bid on time and cost, including cost caps. This ensures the best project plan wins and ratepayer funding is used most efficiently,” says Mr Hertz-Shargel.

The rise of competitive bidding has allowed independent transmission developers, such as NextEra Energy Transmission, to chip away at utilities’ monopoly rights. The group has constructed 1700 miles of transmission lines across the US, and its winning bids for two projects running across Oklahoma, Missouri and Kansas were 40% cheaper than the local network operator, Southwest Power Pool, had forecasted. Its president, Matt Valle, says the company is now exploring high-voltage transmission development across Canada.

Competitive bidding has also allowed cash-rich private equity firms to invest in transmission projects. Blackstone is a prime example: “We can move quicker than the incumbent utilities … we aren’t encumbered by a rate base or the need to manage a capital budget facing multiple demands,” says David Foley, the global head of the firm’s energy business.

Its most ambitious project is the Champlain Hudson Power Express, a $6bn transmission line known as CHPE that will deliver 1.25 gigawatts (GW) of hydropower from Québec in Canada to New York city in the US. The 546km high-voltage cable is being buried in the seabed under Lake Champlain and the Hudson River, and is due to complete in 2026. The project is being developed by Blackstone’s portfolio company, Transmission Developers (TDI), and run in partnership with Canadian utility Hydro-Québec, which pays TDI a capacity payment over 40 years.

Blackstone acquired TDI in 2010 when it was an early stage company underpinned by a visionary management team with an ambitious idea. Five years later, it backed a different group of industry veterans to form GridLiance, which constructed 700 miles of power lines before being sold to NextEra in 2021 for $660m.

Blackstone’s track record of providing risk capital to experienced management teams looking to build transmission businesses illustrates the value of private equity for time-consuming, capital-intensive grid extensions. “So long as we think the returns on capital are there and the team is working to get there, we can be patient and help them with it,” says Mr Foley.

More private capital is expected to be unlocked by the US Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which sees the government commit $10.5bn towards half the value of grid upgrades. “Utilities will probably rely on their ratepayers to match the [remaining] 50%, but commercial entities can also apply, so that will bring some private funding,” says Ms Kazempour.

But in the US, funding is not the biggest hurdle to grid modernisation: “the problem is how long permitting takes and the risks that brings about,” says Mr Richins. It took Idaho Power 16 years to obtain an unappealable permit for its Boardman to Hemingway transmission line in the state of Oregon. “Entities like us end up putting millions of dollars into these permits, not even knowing if it will be constructed or not. And a lot of entities just aren’t willing to take that risk,” he says.

Learning from Latam

The US borrowed the competitive bidding model from Latin America (Latam). Brazil, Peru and Chile have been granting private companies long-term transmission concessions since the 1990s as part of the privatisation of their power sectors. From 1998 to 2016, this model spurred the development of 77,000km of power lines across the three countries, according to the World Bank.

It has also been a magnet for foreign investment. Italy’s Enel owns distribution grids in all three countries, plus Colombia and Argentina. Foreign investors have ploughed $4bn into Peru’s transmission projects, either directly or via local subsidiaries, according to ProInversión, Peru’s private investment promotion agency. Meanwhile in Brazil, Spain’s Iberdrola announced last July it was investing $1bn in the country to develop 1700km of transmission lines to get more renewables online, while Portugal’s EDP is spending $1.5bn on its Brazilian network infrastructure between 2021 and 2025. Moving forward, the country plans to tender $10bn worth of new investment in 2023/24 to develop 14,500km of new transmission lines, according to figures from the energy ministry.

Another country following Latam’s lead and gaining the attention of foreign investors is India. In January, Norway’s development finance body Norfund announced it was partnering with Norwegian pension fund KLP to invest NKr900m ($10.9m) in a transmission line being built by Indian energy giant Renew. It will transport 2.5GW of power from the Koppal district in the state of Karnataka, which has the country’s third-highest wind resource, to the national grid. “It is an important piece of infrastructure to bring more wind resources into India’s national grids,” says Mark Davis, Norfund’s executive vice president for clean energy.

Across Scandinavia, pension funds have invested heavily in their local transmission and distribution companies as they provide steady, low-risk returns. “There’s good predictability and visibility of where cash flows are coming from, and there’s obviously a need for investment and a good setup for how that gets remunerated,” says KLP investment analyst Eric Nasby. To get more pension money into developing countries’ transmission projects, Mr Nasby says it is important to have partners like Renew and the backing of a development finance organisation. “We need the comfort of Norfund and knowing the local developers,” he says. “We couldn’t do this on our own.”

Mr Davis hopes more countries will allow privately funded transmission expansions and says Norfund hopes to do more projects in India. “We would do it in Africa too, if the opportunity arose,” he adds.

Final frontier

In Africa, efforts are underway to do exactly that. In a continent where less than half the population has access to electricity, grid upgrades are driven more by the need to bring people online than by the green transition. But the investment challenges remain the same and are compounded by the majority of grid operators being lossmaking.

Africa’s utilities, which are overwhelmingly state-owned, struggle to get regulatory signoff on their investment plans due to either the population’s inability to pay or political pressure from governments, says Mr Hodson. It means tariffs are often kept below the cost of supply, leaving utilities to absorb the deficit. This has deterred private capital and left grid operators relying on government budgets — which face competing demands — and multilateral funding.

Since its launch four years ago, Gridworks has worked with African governments to create bankable project models to get private capital into the continent’s grids. Its pilot project, announced last year, sees Gridworks finance and develop a $90m upgrade of four substations on Uganda’s grid, which will help absorb electricity from new hydropower projects. Mr Hodson is discussing similar projects with “half a dozen” other governments across eastern and southern Africa.

One way foreign investors have funded African transmission is by connecting their generation projects to the national grid. France’s EDF has partnered with the International Finance Corporation and Cameroon’s government to develop the €1.2bn Nachtigal hydroelectric project, which includes a 50km power line connecting the 420MW plant to the national grid. “EDF has expertise in substations and transmission lines, and is therefore ready to make this expertise available to projects if this is requested,” says an EDF spokesperson, who adds that it can be an opportunity to derisk investment.

However, this arrangement is not guaranteed to succeed, even in developed markets. In 2020, EDP Renewables cancelled a 100MW wind project in the US after the grid operator requested it do $80m worth of upgrades to connect to the network. This was eight times higher than EDP expected and was at risk of increasing further, a spokesperson tells fDi.

While renewable power generators will not always be willing to pay for grid extensions, experimentation like this is needed to reach net zero by 2050. Without new ideas, EVs will not be able to charge and wind power will be wasted. Without transmission, there will be no transition.

This article first appeared in the April/May 2023 print edition of fDi Intelligence.